A German court will hand down a historic verdict on Wednesday in the first court case worldwide over state-sponsored torture by the government of Syrian President Bashar al-Assad.

Almost 10 years since the Arab Spring reached Syria on March 15, 2011, the judgement will be the first in the world related to the brutal repression of protesters by the regime in Damascus.

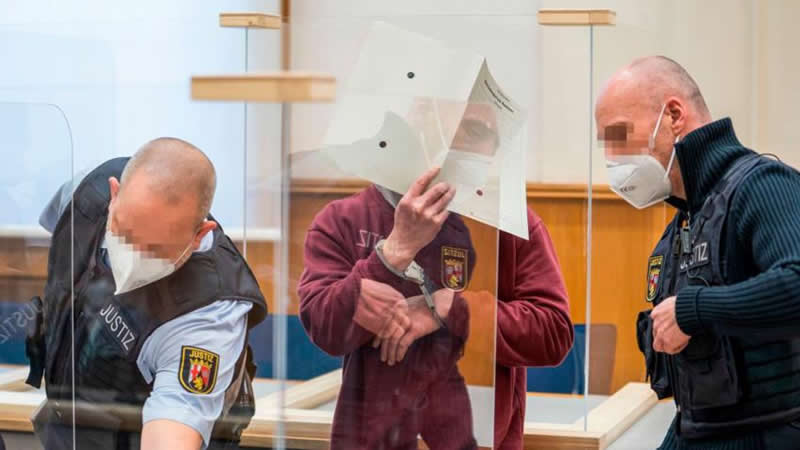

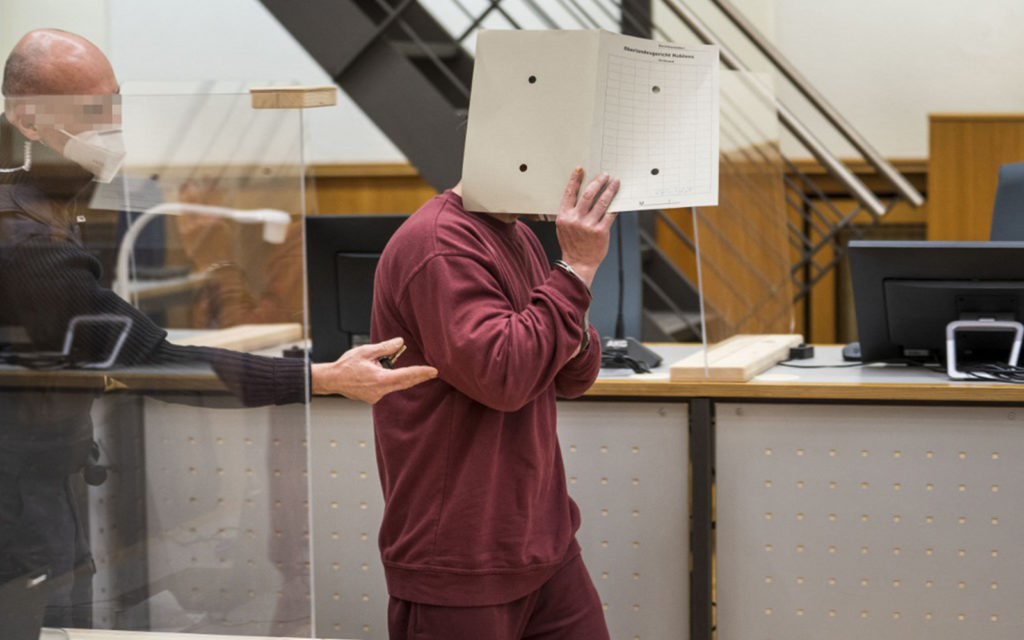

Eyad al-Gharib, 44, stands accused of being an accomplice to crimes against humanity as a low-ranking member of the intelligence service.

The former colonel allegedly helped arrest at least 30 protesters and delivered them to the Al-Khatib detention centre in Damascus after a rally in Duma, northeast of the capital, in the autumn of 2011.

Gharib will be the first of two defendants on trial since April 23 to be sentenced by the court in Koblenz, after judges decided to split the proceedings in two.

The second defendant, Anwar Raslan, 58, is accused directly of crimes against humanity, including overseeing the murder of 58 people and the torture of 4,000 others.

Raslan’s trial is expected to last until at least the end of October.

The two men are being tried on the principle of universal jurisdiction, which allows a foreign country to prosecute crimes against humanity, including war crimes and genocide, regardless of where they were committed.

Other such cases have also sprung up in Germany, France and Sweden, as Syrians who have sought refuge in Europe turn to the only legal means currently available to them to due to paralysis in the international justice system.

Prosecutors in Koblenz are seeking five and a half years for Gharib, who defected in 2012 before finally fleeing Syria in February 2013.

After spending time in Turkey and then Greece, Gharib arrived in Germany on April 25, 2018.

He has never denied his past, and in fact it was his stories told to German authorities in charge of his asylum application that eventually led to his arrest in February 2019.

Prosecutors accuse him of being a cog in the machine of a system where torture was practised on an “almost industrial scale”.

With attention focused mainly on Raslan during the 10 months of hearings, Gharib remained silent and hid his face from the cameras. He wrote a letter read out by his lawyers in which he expressed his sorrow for the victims.

And it was with tears streaming down his face that he listened to his lawyers call for his acquittal, arguing that he and his family could have been killed if he had not carried out the orders of the regime.

His defence also said he lived in fear of his superior Hafez Makhlouf, a cousin and close associate of Assad who was notorious for his brutality.

But Patrick Kroker, a lawyer representing the joint plaintiffs, argued that Gharib could have been more forthcoming during the trial, rather than keeping silent throughout the hearings.

People like him “can be very important in informing us about the (Syrian officials) we are really targeting, but it is something he chose not to do,” said Kroker.

During the trial, more than a dozen Syrian men and women took the stand to testify about the appalling abuses they endured in the Al-Khatib detention centre, also named “Branch 251”.

Prosecutors said they had suffered rape and sexual abuse, “electric shocks”, beatings with “fists, wires and whips” and “sleep deprivation” at the prison.

Some witnesses were heard anonymously, with their faces concealed or wearing wigs for fear of reprisals against their relatives still in Syria.

The trial also marked the first time that photos from the so-called Caesar files were presented in a court of law.

The 50,000 images taken by Syrian military police defector “Caesar” show the corpses of 6,786 Syrians who had been starved or tortured to death inside the Assad regime’s detention centres.

They were scrutinised during the trial by forensic scientist Markus Rothschild, whose analysis constituted overwhelming material evidence.